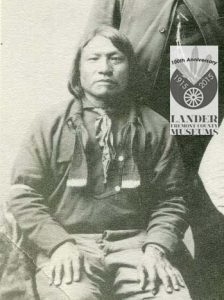

One of the pivotal lives among the Arapaho in the 19th century was a man named Friday. He spoke English and frequently acted as an intermediary between the Arapaho and the Whites. In 1869, Friday told the officers at Fort Fetterman there were 4 principal chiefs of the Arapaho: Medicine Man, Sorrel Horse, Black Bear and himself. Their bands were scattered around Wyoming and numbered about 1000 people. Wyoming territorial governor, John Campbell described Friday as, “an Indian of some education and of considerable intelligence.” His life’s story is worth noting.

In 1831, Tom “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, a fur trader and noted mountain man came across three young Native American boys all alone on the Great Plains in the area of what is today Dodge City, Kansas. The boys were hungry, thirsty and scared. Fitzpatrick took the boys with him to Saint Louis. He took a liking to one of the boys, who was called Warshinum or Black Spot by his people. Fitzpatrick renamed the boy Friday, possibly a reference to the book Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. Friday was enrolled in school, but travelled with Fitzpatrick on his fur trapping expeditions out West. On one of these trips they came across a band of Arapaho and a woman in the band recognized him as her lost son. She claimed him, and Friday stayed with his Arapaho family and resumed his family’s lifestyle. Fitzpatrick and Friday remained close friends until Fitzpatrick’s death in 1854. Friday had spent approximately seven years living among the Whites. What he had learned about the White men became very valuable to his people.

As a youth, Friday worked hard to establish a reputation for bravery including a battle with the Pawnee. He was also an accomplished buffalo hunter often taking several animals in a single chase and was able to use both rifle and bow. These skills and his intelligence helped him to grow into a leadership role as he grew older.

In 1864, Friday’s band camped close to Fort Lyons in Colorado as directed by the Colorado territorial governor. When the Native Americans camped around the fort were told to leave, many of them went a few miles away to Sand Creek to camp. Luckily, Friday didn’t take his band to Sand Creek. The Cheyenne and Arapaho who went to Sand Creek became the victims of one of the worst military atrocities in US military history when peaceful women, children and old men were slaughtered by troops under the Command of General John Chivington. Did Friday recognize the impending danger, or was it just luck? We may never know for sure.

After the Sand Creek Massacre, many Arapaho wanted revenge, but Friday argued for peace and refused to fight the Whites. This stance cost him prestige among his tribe, and his band became somewhat isolated as most Arapaho moved north to Wyoming where there were still buffalo to hunt.

In 1868, Friday was paid $315 to inform the various bands about the peace council at Fort Laramie. Later that Fall, Medicine Man asked Friday, who was camped along the Cache la Poudre River in Colorado to join him along the Powder River in Wyoming. Friday’s band, which by then consisted of mostly older people, was the last band of Arapaho to leave Colorado. With Friday as their interpreter, the Arapaho started lobbying the military and the government to find them a permanent home. They did not want to be placed on the Sioux reservation, but preferred to have their own reservation or to live with the Shoshone.

In 1877, Friday accompanied Arapaho Chiefs Black Coal and Sharp Nose to Washington D.C. as an interpreter to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes. They tried to persuade the President to give them their own reservation.

The Arapaho were temporarily placed on the Wind River reservation in 1878. The Arapaho were happy not to be placed with the Sioux or sent to Oklahoma. The placement became permanent over the objections of the Shoshone, .

In 1881, several Arapaho children were sent to the Carlisle Indian school in Pennsylvania, so they could learn to assimilate into the White culture. They were also held as hostages to ensure their parent’s good behavior. Many of these children died of disease including two of Friday’s grandchildren. Friday died May 13, 1891.

Until his death, Friday worked as an agency interpreter for $25 a month. He and his multiple wives left many descendants among the Arapaho people with a proud heritage. Roughly, thirty-five hundred out of approximately 10,000 enrolled Northern Arapaho trace their lineage back to Friday.